Jessica Lange’s portraits of a lonely city

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I’ve suffered bouts of depression my whole life,” says two-time Oscar-winning actor Jessica Lange. “They ebb and flow. I have a hard time separating the sadness, the depression, from my overwhelming sense of loneliness.”

Speaking from Ireland, where she is filming an adaptation of Long Day’s Journey into Night, Lange again has loneliness on her mind. “I could be feeling that even more acutely right now because I’m starting to play [drug-addicted matriarch] Mary Tyrone again. I’ve gone through the play and counted how many times she says ‘alone’.” High-wire performances in films such as Frances and Blue Sky have also taken their toll.

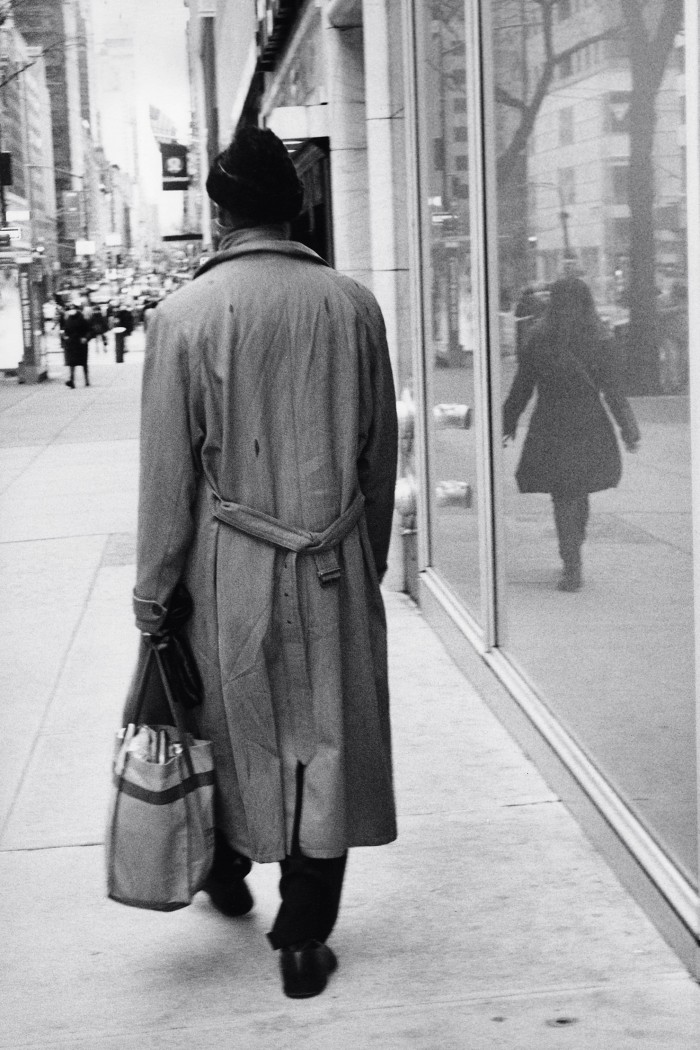

But Lange, now 73, has found solace on the other side of the camera. In Dérive, her third book of photographs, she faces the subject head on, and the result illustrates her talent for diffusing melancholy with a curious eye. The book is a visual account of her walks through New York City during lockdown. On the advice of her son Walker, she practised the art of dérive – or drift – a concept proposed by the midcentury French philosopher Guy Debord in which “one drops all their usual motives for movement and action to let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain”. But rather than exacerbating the pervading mood, Lange found walking aimlessly with her camera “a comfort. Because our usual mode of moving through a city is determined, time-sensitive; we’re not looking,” she says. “People are really in their own worlds. You get a sense of anger. They’re rushing; there’s no time for kindness.”

Lange’s pictures capture a woozy timeless metropolis: grainy shots of the façades of strip joints harken back to the ’70s, other images look like echoes from the 19th century. One features a solitary young girl, dressed in white, standing by a lake. “I had walked up to Central Park that day and there she was like some kind of spectre,” says Lange.

Stripped of its vitality, Manhattan “had an eeriness to it – that I was immediately drawn to”, she says. “It was almost as if it was in suspended animation. It never scared me, but it was unnatural for that city. You could walk for blocks and blocks and blocks and not see anybody.”

From her apartment in Greenwich Village, Lange walked up to 10 miles a day through areas she barely knew. The homeless people she met were anxious to tell her their stories. The result was a “human exchange that I normally wouldn’t have had when the streets were crowded. We were all desperate for someone to talk to”. An assortment of other lone figures also make a connection through the camera – a fishmonger peers over his lobsters, an elderly man smokes a pipe. “You pick up pictures like that and however much time has passed it’s as if they are looking directly at you,” she says.

Photography is an old flame rekindled. Lange grew up in a Midwest sawmill town and, in the late ’60s, long before Tootsie made her famous, took a photography class at the University of Minnesota. She also hung out with Robert Frank and Danny Lyon, giants of American documentary photography. “I watched them work; and I knew friends who had darkrooms in the bathroom,” she recalls. “The enlarger would sit on the toilet. Things would be lined up in the bathtub.”

She was in her 40s when she found the confidence to take her own pictures. Sam Shepard, the actor and writer who was her partner for 27 years until they separated in 2009, gave her a Leica – and her first subject matter was family life. “It started with taking real photographs of [my children]. Not just snapshots like the way people now take thousands of goddamn photos on their phone all day long, no matter what they’re doing, what they’re eating.”

The medium reinvigorated her. “It was something that I needed at that time. To wake me up. I built a darkroom in the house and started shooting and developing my own film and printing.” She finds succour in its magic. “When you shoot a roll of film, it’s like a great mystery… That thing of looking at the contact sheets for the first time – it still thrills me. When you’re developing a photograph and that image just seems to come up, it’s like alchemy.”

In conversation, Lange has the jolly-but-sharp appeal of a country girl with street smarts. But for four decades, both on screen and in theatres, she has perfected the cracked-porcelain persona. “I find I’m drawn to characters that live life in extremes,” she says. “I’ve played characters who are kind of on the tightrope between madness and sanity. Like Blanche DuBois and Frances Farmer.” A similar tension can be found in her photographs.

While the camera delivers an antidote to her depression, it also acts as a corrective to the bustle of cinema. “Because acting is such a communal effort. Photography was something I could do by myself.” There is both reflection and independence in taking pictures, she explains: “This is what dérive felt like to me, like a walking meditation.”

Dérive by Jessica Lange (powerHouse Books, $60)

Comments