What a twinkly beard can teach you about investing

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

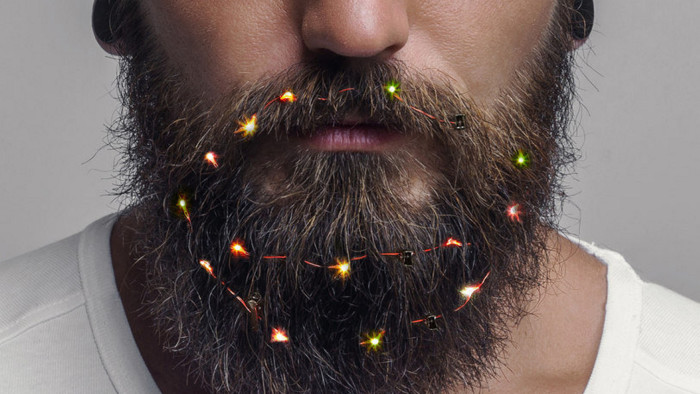

This season’s must-have accessory is multicoloured Christmas lights for your beard, or the beard of the man in your life. But at around £10, how do you determine if it is good value? It depends how much you want a twinkly beard in your life, and if there is a beard around to accessorise.

This is an excellent example of a product only being worth what someone is prepared to pay for it. For the avid beard light wearer who values “being both intensely masculine and adorably festive”, it represents a bargain. Particularly, if it gets him noticed by the boss at the Christmas party, which leads to a promotion. (This may only work in the creative industries. In a traditional wealth management firm, sporting LEDs in one’s beard may be damaging at bonus time.)

For twinkly beard’s girlfriend, the accessory may be drastically overpriced tat. She likes to focus on “quality” and is saving for a £4,000 Hermès Birkin handbag, which she believes will be an investment purchase. A 2016 study famously showed the £150,000 Hermès bag has averaged a 14.2 per cent annual return since 1980, beating the S&P 500 index and gold. Since the release of this study, the Hermès Birkin has smashed the world auction record several times, with one vintage bag selling for a record £162,500 in London this summer.

Overpriced tat can have its moments too, though, points out the bearded boyfriend, even over short periods, with some rare Pokémon cards fetching thousands of dollars and sealed Transformers figures from the 1990s being popular with collectors. If the beard lights also produced a 14.2 per cent annual return, the neat investment Rule of 72 (years to double = 72/interest rate) shows they could double in value in five years.

Although buying both beard lights and handbags could be called, for different reasons, “investment purchases”, and could make you wealthier, it is a risky strategy. If you can afford a portfolio of handbags, diversified by brand and stored in a vault somewhere, you’d lower the risk. But if you only have one handbag, you may have it stolen, spill coffee on it or find that it’s the one that goes out of fashion just at the moment you need to sell. I wouldn’t define material purchases that can deteriorate with use and time as real investments. They may be savvy rather than frivolous purchases, but the savvier thing is to own a share of the business that produces the goods in the first place.

So, what makes a real investment? One good definition is an ownership stake in a business or asset that has potential to grow in value, while paying you an income while you wait for it to grow. This would include a FTSE 100 company or an investment trust that pays its shareholders dividends, or a buy-to-let property that generates rental income (more difficult to find now that the government has imposed extra taxes). If you don’t need the income, then you roll it up by buying more of the investment over time.

Growth investing is different. It involves spotting companies that exhibit signs of above-average growth, even if the share price appears expensive. Lots of well-known companies on the stock market started with big ideas and dreams but no cash, very little revenue and constant operating losses. Facebook and Amazon began that way, and some big companies even started with ideas not related to their business today — Groupon and Instagram.

Meanwhile, plenty of rivals went under along the way. If you spotted a cheap start-up that survived and grew, were you lucky or prescient? Could Firebox.com, which was selling the beard lights, be the next one? In fact, how do you determine value in any investment when it’s still, like a handbag, only worth what someone is prepared to pay?

The efficient market theory — that all information related to an asset’s value is instantly reflected in the price — became popular in the 1970s and spawned index tracker funds, which buy all the shares in a benchmark index like the FTSE 100.

But many investors believe that they can beat the market by profiting from the irrational decisions of others or spotting opportunities that others missed. This is why we have a proliferation of professional fund managers all looking to beat the market.

Many fund managers say there’s no substitute for fundamental analysis, which means evaluating the balance sheet and factors such as the price/earnings ratio, as well as meeting the company’s management. It is often called “bottom-up analysis”, where you choose individual companies regardless of wider prospects for the economy or sector.

But it’s not the only way to invest. Others choose assets based on a big theme such as technology — looking at sectors that they expect to flourish. Contrarian fund managers choose assets that are out of favour. Income fund managers buy stocks with a strong record of earnings and dividends. And you may find one fund manager using a range of these strategies.

All of this makes it difficult to spot value when investing using funds — you may be able to get an overview of the strategy from the fact sheet or website, but you’ll never know exactly what strategies the fund manager is using today.

I think value hunting is much easier when using investment trusts. Here you have the discount and premium to take into consideration. This shows when the price of the investment trust’s shares is less or more than the net asset value of the underlying holdings. To identify a bargain, you can compare current discounts with longer-term averages.

On Black Friday, F&C UK Real Estate Investments, Tritax Big Box and Woodford Patient Capital were among trusts that looked like bargains on this measure. While in September, customers of interactive investor were snapping up relatively unloved UK equity income trusts such as City of London and Finsbury Growth & Income, which looked cheap relative to their global peers.

Meanwhile, is value everything? Some investors prefer to look for investment trends instead. And one of the biggest trends could be about to occur. Investors are awaiting the Santa rally — the festive term applied to the phenomenon of rising markets in December — which could give as much of a seasonal boost to your investments as a twinkly beard can give to your ego or a handbag to your wardrobe.

Over the past 20 years, the Santa rally has happened every year without exception (based on comparing the December low of the FTSE 100 going back to 1998 with the relevant December high). It also appears that the market likes to finish the year on a positive note, with the highest day of the month falling in the trading days between Christmas and the new year in 19 of the 20 years. That’s 95 per cent of the time, which is more than enough to make me feel twinkly about investing in the festive season.

During the writing of this article “due to phenomenal global demand” the beard lights sold out. I’ll be advising the bearded folks among my friends and family to avoid the beard baubles that Firebox.com presents as an alternative, and buy the iShares Core FTSE 100 ETF instead. Even if we don’t get a Santa rally, you’ll have the yield of 4.23 per cent.

Moira O’Neill is the head of personal finance at Interactive Investor. The views expressed are personal. Twitter: @moiraoneill

Comments