The protectionist president who’s good for trade — for now

Simply sign up to the US trade myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

FT premium subscribers can click here to receive Trade Secrets by email.

Hello from Brussels. This is the last week before Trade Secrets is revamped next Monday, when we’ll be featuring more charts and a fresh section on the best content the internet has to offer on globalisation. As always, we’d welcome your thoughts on what you’d like to see more of from us.

My colleagues here are working on an intriguing EU trade story, due out this afternoon. Watch this space.

They already have a story up about the EU being optimistic that a bunch of issues with the US — Airbus-Boeing, American tariffs on European steel and aluminium exports, Brussels’ plans for a dedicated transatlantic discussion forum on trade and tech — can get sorted. It has to be said, though, that while the Biden administration’s first 100 days have seen engagement on trade, it’s not exactly been a breakneck rush to get all the problems fixed. On that subject, today’s main piece is on why a protectionist US president with some entirely wrong-headed ideas about reshoring and economic nationalism might start off as one of the better things that’s happened to world trade for a while. “Start off”, however, is the operative term. It’s got plenty of potential to fall apart before too long.

Tit for Tat marks China’s 20th anniversary as a member of the World Trade Organization.

Don’t forget to click here if you’d like to receive Trade Secrets every Monday to Thursday. And we want to hear from you. Send any thoughts to trade.secrets@ft.com or email me at alan.beattie@ft.com

The sweet spot of a stimulus without Buy American

There’s an uncomfortable amount of truth in the view that President Joe Biden shows more continuity than change from Donald Trump on trade. So far his administration has kept in place Trump’s Section 301 tariffs on China and even the bonkers national security Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminium, including from the EU. This leaves Biden in the bizarre position of calling for strategic alliances with European countries that his trade policy says are a threat to American national security. Moreover, in both his rhetoric and some of his appointments, the president is continuing Trump’s obsession with reshoring and made-in-America.

If not actually more protectionist than Trump, Biden has very definitely shifted from the approach of Barack Obama (even if Obama was less a convinced free-trader and multilateralist than sometimes assumed) and that of Bill Clinton.

If Biden follows through with a big expansion of Buy American procurement provisions in his promised Green New Deal for the US economy, forced reshoring of supply chains and clumsily executed tech conflict with China (a big “if”, there’s a long history in the US of fighting talk being followed by pragmatic actions), then it’s clearly bad for the world trading system.

But his first big action hasn’t been protectionist procurement or a new round of tariffs. It’s been a whacking great $1.9tn stimulus, which is likely to boost trade.

The OECD reckons Biden’s stimulus will put nearly 4 percentage points on US GDP growth this year. Cyclically, world trade and GDP tend to move together, and the latter tends to drive the former. Trade, at least goods trade, crashed during the global financial crisis in 2008-09. Was that a result of widespread protectionism? No: it was a huge collapse in demand. And as it happens, US public sentiment towards trade and globalisation seems to move according to the economic cycle of the economy rather than trade policy as such.

The nature of the stimulus matters. Biden has clearly learned from earlier episodes: as Obama found in his first year in office, programmes based on trying to find shovel-ready projects generally end up either being late and ineffective stimulus or building bad infrastructure. The promised greening of the economy will have to wait.

Instead, the initial Biden stimulus is all about funding the Covid-19 vaccination programme and spraying cash around to state governments, families and businesses. Unlike the Trump tax cuts to the rich, which didn’t do much for growth, that money is overwhelmingly likely to be spent rather than saved, and a chunk will ultimately be spent abroad: the OECD reckons the package will raise global GDP growth by 1 percentage point this year. Other countries might not like the idea of Buy American or Section 232, but for the moment they might well decide to shut up and enjoy the exports. (Whether you think the stimulus will raise the long-run level of GDP depends on whether you believe in hysteresis, or the permanent impact of temporary factors, but let’s not get into that right now.)

Trade policy certainly influences longer-term prosperity. Countries following boneheaded isolationist strategies will struggle to raise trend growth. Yet in the shorter term, its macroeconomic effect is not generally overwhelming. Trump’s trade war inflicted probably the most radical negative policy shock to the system since at least the 1970s. The measurable impact? Maybe half a per cent off the level of US GDP, a loss of about 250,000 jobs out of a workforce of about 150m. Not catastrophic.

It’s only in future years that the wrong-headed protectionism of the Biden platform is more likely really to come through — specifically in the Buy American provisions promised in the proposed infrastructure bill, and in the pledges to restructure supply chains to bring more production back home. This has the potential to do serious damage. If Biden goes in with a strong prejudice that, as he said last week to Congress, the blades for wind turbines should be made in Pittsburgh rather than Beijing, the US will very likely waste money, and end up with kit that is more expensive and takes longer to deliver: bad for growth, bad for trade, bad for the greening of the US economy. Money spent inefficiently is also more likely to generate price rises than jobs.

If you’re braced for a big hit to world trade in the short run from the US, you’re liable to be pleasantly surprised. The effect of the Biden stimulus, on top of the general recovery from the pandemic, are going to be pretty good for globalisation this year. Enjoy it while it lasts. There’s plenty of potential for everything to go wrong before too long.

Charted waters

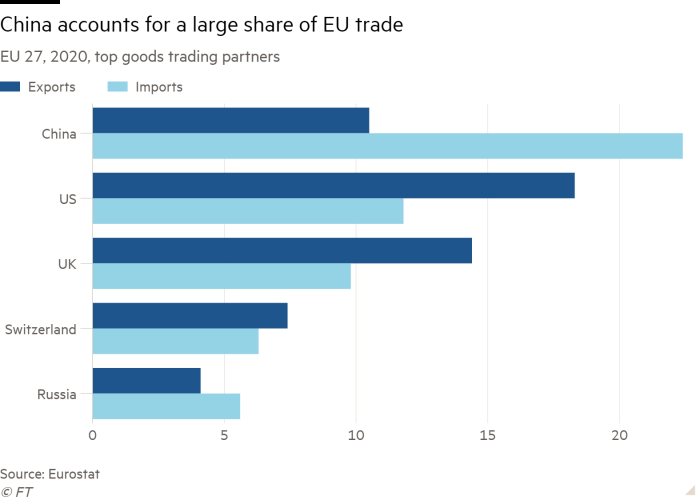

Today’s Tit for Tat examines the effects of China’s accession to the WTO, one of which has been to make Beijing one of the most important trading powers in the world.

The trading relationship with China has become especially important for the EU, with some fairly politically charged consequences (as we’ve written about here and here, to pick but two of our regular pieces taking issue with the bloc’s Comprehensive Agreement on Investment).

When it comes to the hard data, here are the latest figures, courtesy of Eurostat, the European Commission’s statistics bureau, which show that China is by far the most important importer. As the country becomes more prosperous, we’d guess it will only be a matter of time before it becomes a top export market too. Claire Jones

Tit for tat

We caught up with André Sapir of Universite Libre de Bruxelles and Columbia Law School’s Petros Mavroidis to ask three questions to mark the 20th anniversary of China’s membership of the WTO later this year.

China joined the WTO in 2001 with great fanfare. Has its accession lived up to its billing at the time?

China has certainly contributed a lot to the expansion of global trade, rapidly becoming the world’s largest exporter and second-largest importer of goods. China’s fast integration in the world economy has brought important economic gains, but also created clashes with western trading partners, partly due to its economic system. In 2001, these countries had expected that China’s economic system would gradually converge to their liberal economic system after its accession to the WTO. In fact, China never committed to become a “market economy”. It only vowed to become a “socialist market economy”. Unfortunately, western countries seem to have only paid attention to the words “market economy”, not realising that for the Chinese the word “socialist” was equally important and that it meant that the state and public ownership would remain central to China’s economic system, no matter what. This hard reality has now painfully sunk in.

The US and Europe continue to have concerns as to whether China is playing fair. What do those concerns centre on?

Concerns with China by the US and Europe centre on two main issues: the way state-owned enterprises (SOEs) operate to provide subsidies to Chinese exporters; and the de jure or de facto obligation for foreign investors in China to enter joint-venture agreements with Chinese companies that force their foreign partners to transfer technology to them without adequate compensation. These two concerns reflect relatively little the fact that China does not respect its WTO commitments or WTO rulings when it has been found to violate them. Instead, they reflect the fact that WTO rules are predicated on a liberal understanding of the role of the state in the economy, which does not apply to China. Given that China is unlikely to change its economic system anytime soon, this means that current WTO rules need to be adapted to deal with those two concerns.

How can the problems be overcome in a way that is both realistic and meaningful?

It is easier to respond to the “meaningful” part of the question. In a recent article and book, we advanced arguments in favour of “completing” the current WTO contract, inspired by disciplines on SOEs and transfer of technology, already included in some free trade agreements and in the EU-China Comprehensive Investment Agreement. Case law has not risen to the challenge, in part because WTO adjudicators are not at ease when dealing with legal concepts imbued with economics sophistication. Pre-empting the discretion of adjudicators by having WTO members “complete” their contract seems warranted. Is a renegotiation realistic? We are cautiously optimistic. China has profited enormously from its participation in the WTO. The cost of non-WTO, as may happen if the “China problem” continues to poison the atmosphere at the WTO, would be felt in Beijing probably even more than elsewhere. China should have an incentive, therefore, to act as a “responsible stakeholder”.

Don’t miss

Janan Ganesh spars with globalisation’s discontents.

Read moreThe chief executive of India’s Serum Institute, the world’s biggest vaccine manufacturer, has warned that shortages of jabs will persist for months after Narendra Modi’s government failed to prepare for a devastating second coronavirus wave.

Read moreAustralia’s department of defence is reviewing whether to scrap a contentious lease to a Chinese company of Darwin port, which is located close to a US Marines base.

Read more

Comments