Carbon counter: petrol vs hybrid vs electric

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Carbon counter is a series of Lex articles estimating the climate cost of different lifestyle choices. The other articles are here.

Transitional technology is a problem for consumers. Why buy a product such as a hybrid vehicle whose obsolescence is a question of “when” not “if”? The dilemma is worsening. Belatedly, traditional carmakers are bombarding the public with adverts for hybrids, a sector once dominated by the Toyota Prius, with plug-ins a new part of the offer. Simultaneously they are promoting full electrics, a category where, for years, it was a Tesla or little else.

What should motorists do? With family cars, as with so many things, carbon savings sometimes come at a financial price.

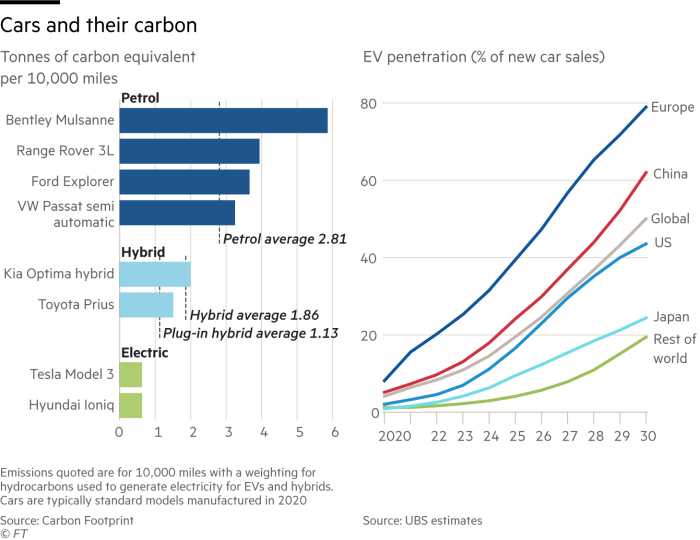

The Tesla Model 3 costs over $39,000 new (UK: £41,000). Its emissions are very low, even if you include a weighting for hydrocarbons used to make electricity, as consultancy Carbon Footprint does. Drivers generate less than a tonne of CO2 for driving 10,000 miles. That is a midpoint between the average annual mileages of US and UK motorists. The carbon burden for the old Volkswagen Passat, a comparable petrol car costing about $24,000 (UK: £25,000) is a whacking 6.5 tonnes.

You can shave off almost half of that carbon with a traditional hybrid. Even more with a plug-in hybrid recharged with mains electricity. The average carbon burden is about 1.1 tonnes for 10,000 miles, according to Carbon Footprint.

Yet Professor David Bailey of Birmingham university is sceptical about hybrids: “Why haul around an engine you mostly do not use?” One reason might be the lower cost of a smaller battery. However, UBS reckons the price premium for electric vehicles over petrol cars will disappear by 2024. The bank expects better manufacturing to cut the cost of batteries to the magic figure of $100 per kilowatt hour.

There are two main conclusions. First, if you are better off, deeply green and can recharge at home, you might as well go electric now. Carbon Footprint’s John Buckley, who is installing solar panels to charge his Tesla, “cannot recommend this enough”. Second, if you are on a tighter budget, prefer to lag behind mainstream trends and live in an apartment, you may want to pause before shifting from petrol to electric. By avoiding a hybrid stepping stone, you may be able to save both money and CO2.

Lex is interested in hearing from readers. Have you considered switching to a hybrid or are you willing to pay more for an electric vehicle?

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Letter in response to this article:

Even diligent hybrid users will struggle to cut CO2 / From Julia Poliscanova, Senior Director for Clean Vehicles, Transport & Environment, Brussels, Belgium

Comments