Children need action not warm words on learning poverty

Simply sign up to the Education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In my years working with the charity Save the Children, I was often humbled by parents and children in the most desperate circumstances keeping alive the hope that comes with education. One 12-year-old refugee from South Sudan told me: “Education is everything — nothing will stop me getting back to school.”

The contrast with the international effort to shield education from the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic could not be more striking.

The hopes of millions of children and the human development of nations hang in the balance. The secretary-general of the UN has warned of a “generational catastrophe” in education. Yet the decisionmakers shaping the pandemic response have been gripped by collective inertia. We need decisive international action.

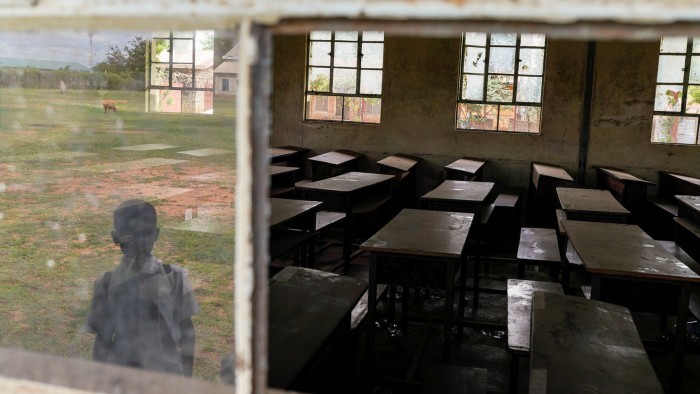

The pandemic did not create the learning crisis. Half of 10-year-olds in the poorest developing countries were already unable to read and 260m children were out of school. Those numbers will now surge. While rich countries, and children from wealthier homes in poor countries, turned to online learning, those on the wrong side of the digital divide have been left behind.

Unesco estimates that, without remedial action, learning losses could eliminate the gains of the past two decades. The World Bank warns that the ranks of children living with “learning poverty” will swell as literacy and numeracy losses accumulate. Coupled with rising child poverty and malnutrition, these learning losses are a prescription for mass dropouts from school.

Today’s setbacks are tomorrow’s inequalities in human development. Education is a catalyst not just for economic growth and job creation, but for progress on poverty, child survival and gender equity.

Identifying the antidote is not hard. Cash transfers and school feeding programmes can help tackle child poverty and malnutrition. More early childhood support would shield the next generation. Assessments for children returning to school, a focus on foundational literacy and numeracy and investment in remedial education can assist recovery.

These are all areas in which international co-operation could “build back better” education systems. Governments of developing countries carry the primary responsibility for delivery. But with recession and debt eating into their budgets, co-operation matters, not least in closing a pre-pandemic aid financing gap in the poorest nations, estimated by Unesco at $39bn.

The international response has been muted. There has been much talk. Unesco convened a Sustainable Development Goal education steering committee and a global education meeting, with hundreds of participants. The product: a vague set of reflections.

An attempt to develop a cross-agency campaign — Save our Future — between UN agencies, the World Bank and non-governmental organisations (disclaimer: I was part of it) produced a powerful report, but no action plan. Has any of this made a difference on the front line? I doubt it.

No additional financing has been provided. To its credit, the World Bank has front-loaded spending from its International Development Association (IDA) facility for the poorest countries. But that is not new money. Donor pledges at the UK-hosted Global Partnership for Education fell far short of the $5bn target.

Unesco warns that bilateral aid for basic education could fall this coming year. In an example of the mismatch between rhetoric and reality, Boris Johnson, the UK prime minister, slashed the aid budget for education while declaring his allegiance to the cause of “12 years education for every girl”.

Far more could be done to use the resources and influence of the IMF and World Bank. Gordon Brown, the former UK prime minister, wants donors to finance education-related loan guarantees through the mooted International Financing Facility for Education. With over 20 low-income countries spending more on loan servicing than primary education, unpayable debts should be converted to investments in children. Donors should increase funding for the IDA, with 8-10 per cent allocated to education.

In some ways the response was predictable. International co-operation in education has long been hampered by the overlapping remits of UN agencies and the World Bank, institutional squabbles and rivalries over funding.

That is not to disparage the excellent work of individual agencies. What is missing is an ability to set a shared vision, agree priorities and roles, co-ordinate support behind governments, and hold institutions accountable. That will take political leadership of a high order in the UN, the World Bank and through the G20.

Persuading large institutions to change course will not be easy. But as Winston Churchill put it: “However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.” As millions of children at the sharp end of the education crisis would testify, the results are not good enough.

Kevin Watkins is visiting professor at the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa at the London School of Economics and former head of Save the Children UK

Comments