Nigerian women face their fears and start using contraception

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Imifioluwa Ajayi is an A-grade student with a passion for maths. A year and a half ago, at 16, she was planning to go to university, study statistics and become a professor. Then she discovered she was pregnant. “I never expected it to come like that,” she says of her baby, “but I would never abort.” She gave birth to her daughter and began using contraception — an injectable hormonal birth control called Sayana Press, that lasts for three months and costs N500 ($1.38) a shot.

At first, like many of her peers, Ajayi was hesitant to use birth control. “Most people are actually scared of it,” she says, sitting in the Planned Parenthood Federation of Nigeria clinic in Ibadan, a southern city a two-hour drive from Nigeria’s commercial capital of Lagos. Ajayi had heard horrible rumours about contraception — that it didn’t work, had gory side-effects or caused infertility. Other teens spread the ominous idea that using it was like working against God. But after using the injectable for months now, Ajayi knows better.

“The Bible says if a man doesn’t know how to cater for his family, then the man is a devil,” she says. The aim of using contraception is not to stop having children but to take better care of the ones you have, she says. “I think women are into family planning because they want a better life for themselves, otherwise it will be a miserable life.”

Ajayi one of a small but growing number of converts, according to Planned Parenthood’s south-west regional director, Elizabeth Abimbola. On a drizzly August day, the modest clinic with yellow walls has the placid ambience of a small library. A retro-style poster near the entrance depicts a heavily pregnant woman carrying a baby on her back and holding the hand of a toddler. It asks: “Why carry more burdens? Plan your family.” A small group of women, most of them wearing gold wedding rings, are waiting on blue plastic chairs to see the medical officer on duty.

There are myriad options on offer, such as birth control pills and implants that can be fitted under the skin of the upper arm, but Abimbola says most teenagers opt for Sayana Press, a lower-dose version of Depo-Provera, another injectable contraceptive, developed by Pfizer and approved for use in 2011 by the MHRA, the UK’s medicines regulator, that prevents ovulation for three months. The smaller needle makes the injectable option “less painful”, says Abimbola, and more importantly there is an “easier return back to fertility: almost immediately” — a plus for a woman in a society that places a premium on having children.

Sexual education in Nigeria is sparse, often non-existent, so Planned Parenthood dispatches youth outreach teams to schools in the cities and far-flung rural areas, offering premarital sexual counselling and free contraceptives to those who want them. Studiously avoiding mention of abortion — which is illegal in the country — they emphasise that contraception allows girls to pursue a career and have a family. It can be the deciding factor between a life of poverty and one of prosperity.

“You can be well educated as a woman, have a good job and have a good home,” Abimbola says, “[and] know that you can still marry and still have children — but when you so desire to have them.”

In some ways, this is still a radical idea in Nigeria. Even though the average age of first sexual intercourse is around 15, according to the World Bank, in many communities talking about sex before marriage is taboo, while contraception is believed to encourage promiscuity. Usually, women marry young and children come quickly afterwards. The median age of first marriage for women is 18, according to Nigeria’s 2013 Demographic and Health Survey. In the north, where teenage girls are more likely to drop out of school, the figure is even lower, with girls in the north-west state of Zamfara first marrying at age 14. Almost 50 per cent of Nigerian women will have given birth by the time they are 20; a Nigerian woman will have five children in her lifetime on average. Despite high levels of poverty and the health risks of back-to-back births, only 15 per cent of married women use contraception.

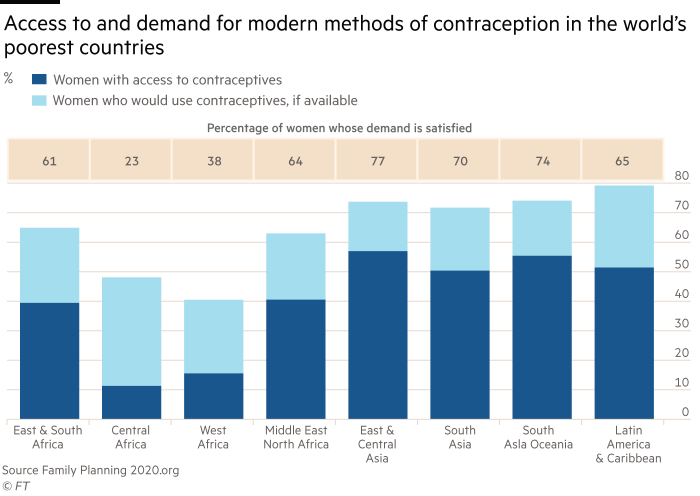

On the surface, it appears the Nigerian government supports family planning initiatives. In July, it pledged to achieve a contraceptive prevalence rate of 27 per cent for women within three years and allocated more money for contraceptives as part of its commitment to Family Planning 2020, a global partnership supporting the reproductive rights of women and girls.

“[For a few years] there has been a real commitment to family planning, which wasn’t the case before,” says Eugene Kongnyuy, deputy representative of UNFPA, the UN population fund. Still, progress is slow, says Anne Austin, an analyst at John Snow, a public health research organisation based in Boston in the US, who has researched contraception use in Nigeria. “Despite policies and programmes that have specifically targeted adolescents, very few have reached the ground at scale,” she says. “Even if contraceptives are available, affordable and acceptable, until communities accept that adolescents may be engaging in sexual behaviour, and support them accessing contraceptives, there will always be barriers to use.”

Changing attitudes towards contraception is not straightforward in Nigeria, where influential religious leaders argue that big families are a God-given right. When former Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan backed birth control in 2012, saying people should only have the number of children they could afford, he was swiftly condemned by both Christians and Muslims.

“We are extremely religious people. It is a very sensitive thing,” Jonathan said at the time, “so it is difficult for you to tell any Nigerian to number their children because it is not expected [that you] reject God’s gifts.”

Many Nigerians are sympathetic to that view: 54 per cent — the second highest number in the world behind Pakistan — say contraception is immoral, according to a 2014 study from the Pew Research Center, a Washington DC-based think-tank. Some critics argue that foreign-funded family planning programmes are a western imposition and a form of population control that undermines an African woman’s autonomy.

As Nigeria’s population explodes, there is growing attention paid to controlling fertility. By 2050, the country’s population is expected to soar to 410m, surpassing the US to become third most populous country in the world, according to a UN report released this year.

Investors initially forecast that, like Asia before it, Nigeria would start seeing a “demographic dividend” — economic growth driven by a massive cohort of youth. Yet with chronic unemployment, an education system in chaos and an indefatigable Islamist insurgency, Nigeria’s population boom is now more often described as a demographic disaster.

Obianuju Ekeocha, president of Culture of Life Africa, an anti-abortion organisation, says “that is a colonial way of thinking”. She argues that contraception campaigns backed by western governments and non-profit bodies result from “misguided compassion” that ultimately strips Africans of their self-determination. “We are not stupid — we know this is the number of children that they want,” she says.

But Ajayi, the aspiring statistics professor, wants far fewer children than the seven that is Nigeria’s average desired family size; she wants a “maximum of two”. Her priority is to give her one and a half year-old daughter the best education possible, she says. Ajayi says she might have another child in five years, but until then she will be using contraception. “Every child is a blessing,” she says, “but giving birth to children without money to care for them is another thing entirely.”

Comments