Investing to beat the inflation monster

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

To investors, inflation is the monster under the bed which suddenly became real. For 30 years we have been able to ignore its menace. But now, with prices rising by more than 10 per cent a year and the best fixed-rate savings accounts delivering less than 5 per cent, your cash will halve in value in 14 years. We cannot close our eyes and pretend it is not there.

This may change the way you view your investments, as well as your risk perceptions. Holding cash has suddenly become less safe. Equities are said to offer long-term protection against inflation, but it is worth understanding how.

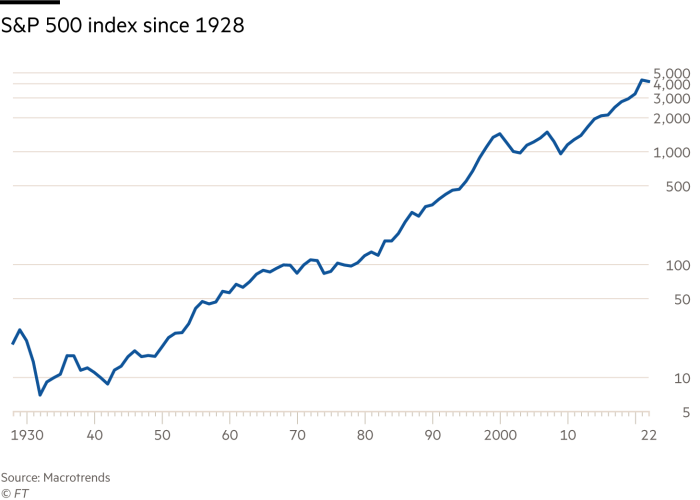

A chart of the S&P 500 from 1927 to today in logarithmic scale shows the performance of the world’s biggest market over nearly a century. The logarithmic scale allows you to spot more easily the market traumas — the Wall Street Crash, the 1974 oil crisis or the 2007-8 Great Financial Crisis. Over the long term the index rises — and you can see how since 2009 it has risen very nicely indeed. But there are long spells where the trend is essentially horizontal.

Take January 1973 to July 1984. The S&P 500 staggered from 120 to 62.28 in October 1974 before gradually clawing its way back up again.

What happens when you factor inflation into the numbers? The story is even bleaker. Adjust prices for double-digit inflation in the early part of this period and it was July 1987 before the S&P price recovered.

The gloom you would expect in this period is reflected in price/earnings ratios, which experienced a similar slow-motion tumble and recovery — from 14x earnings to 7x and then to 20x.

Yet the total return with dividends reinvested over those 14 years was nearly 400 per cent — about 11.6 per cent a year. Adjusted for Consumer Prices Index inflation, these returns look more modest — 86 per cent in total and 4.3 per cent a year in real terms — but still a lot better than the index charts alone might imply. And this is a real return.

As we find ourselves in a new period of inflation and volatile markets, there is an important lesson in these numbers. Dividends count. They are likely to become a much bigger part of total shareholder returns if we are in for a long period of market stagnation.

So far this year the S&P 500 is down 24.49 per cent in dollar terms. Many of the companies we hold have seen their share prices stumble. But, as an investment trust with a focus on income, we have been paid 4 per cent to 5 per cent in dividends, which has made a significant contribution towards total performance and should continue to do so.

The dangers of doomsaying

Investors need to avoid dividend traps — companies that pay large yields but are flawed and heading for the rocks. Looking at today’s market, though, in my view, pockets of valuation anomaly are emerging.

The relative price of “safety” appears to be rising. The valuations of many consumer staples, utilities and some elements of healthcare now look extended, particularly when plotted against those of lowly-valued sectors like banks, consumer finance and autos.

Pepsi, a company we admire and whose shares we hold, recently reported pricing up 17 per cent. This is comforting for shareholders, but how sustainable is it? Pepsi shares trade on 24x consensus earnings for next year — in other words, at a 50 per cent premium to the market.

If you are still buying staples and utilities, you probably need to be confident that we are going to endure a major recession.

We put a lot of trust in the data and forecasts, but they are not always reliable. Norman Lamont was the last UK chancellor to handle high inflation and recession, in the early ’90s. As he ruefully reflected many years later: “I was led to believe we were enduring the worst economic crisis in our history. Later, as the figures were constantly revised and revised, it turned out that it was one of the shallowest!”

Widely mocked at the time for identifying green shoots of recovery, he was probably right. It is easy to be too gloomy, and, as investors, we have to anticipate economic pivots.

To that end, we have recently been eyeing up consumer discretionary stocks, like retailers, housebuilders and carmakers.

Everyone says the auto sector performs badly in a recession. But it has been in a recession for two years already because of the crisis in the supply of semiconductors. Global inventories are close to the lowest they have been in 30 years. The number of vehicles sitting in US showrooms, distributors and factory lots is around a tenth of what it was in 2016. So this is not a sector that has been over-earning.

We have owned VW shares for some time. The company recently listed a 12.5 per cent stake of non-voting stock in its most profitable brand, Porsche. Based on the price of those shares today, VW’s remaining holding in Porsche is valued at just over €61bn. VW itself is valued at €78bn. Essentially, you are getting VW, Audi, Škoda, SEAT, Lamborghini, Bentley and Ducati for around €17bn. The company is on a price/earnings ratio of 3.5, yields around 7 per cent and has cash reserves of €25bn.

Stellantis, the multinational manufacturer created last year from the merger of companies like Fiat, Vauxhall, Citroen, Peugeot and Chrysler, is not a stock we own. It currently trades on less than three times earnings and yields 10.5 per cent. It has net cash on the balance sheet of €22bn.

Yes, there is the worry about electric vehicles and whether these companies will manage the transition. Car manufacturers can trade on relatively low price/earnings ratios. But you do not have to make heroic assumptions to see how you might make above-market returns from companies in this and similar sectors.

If you have a well-balanced portfolio, with some companies on sensible valuations paying an acceptable dividend and still growing quickly, a few lowly-valued companies paying a high income can be attractive — as long as you are confident of being paid.

That is the crucial issue. Some of the consumer discretionary stocks I am looking at currently — in several areas — should be able to sustain high dividends almost irrespective of what goes on in the world.

And if the economy takes a positive turn there is the possibility of equity growth, too. We are not abandoning our defensive positions, but in a world of incessant gloom some of these higher-yielding stocks could offer valuable dividend income — as well as growth. Think of it as insurance against good news. Investors are not defenceless in the battle against the monster of inflation.

Stephen Anness is manager of the Invesco Select Trust plc Global Equity Income Share Portfolio

Comments