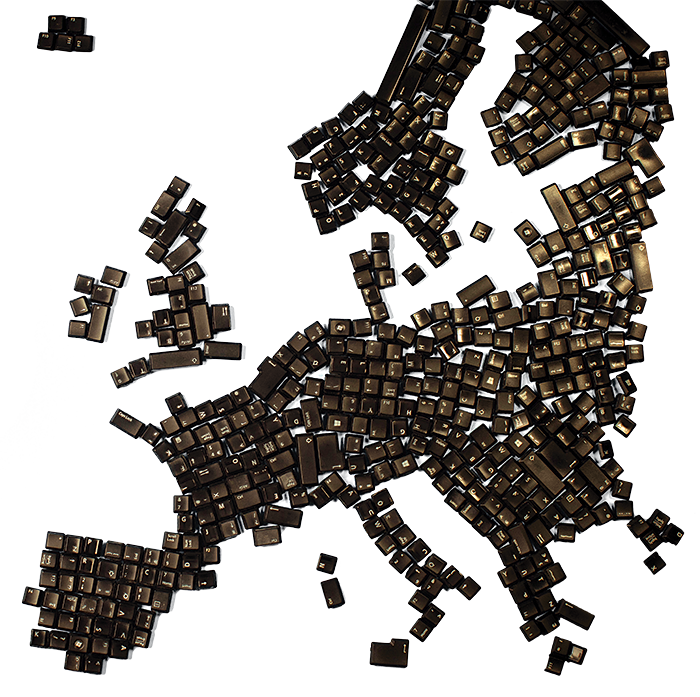

Europe plays catch-up in digital innovation

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Europe faces an innovation gap. Despite being home to some of the world’s leading engineering and pharmaceuticals groups, it lags the US and China in applying digital technology to a fresh generation of products and services. Companies such as Alphabet, Facebook, Alibaba and Tencent — global leaders in consumer technology — were all founded outside Europe.

But there are signs of change across the continent. Europe has a strong record of research and development, accounting for 20 per cent of global R&D spending. Venture capital has poured into start-ups and growth companies, with clusters forming in cities from London to Paris and Berlin. Incumbents, facing disruption in their industries, are adopting new approaches.

The Europe’s Road to Growth project starts from the principle that the continent still needs to accelerate if it is to rival digital innovation elsewhere in the world. That will require a change of approach — not just by creating start-ups but by building on Europe’s strengths, including its universities, scientific research and a trained workforce.

The project looked for leading examples of companies changing how they operate to grow faster and identify new customers. Incumbents face the trickiest task — not starting with a blank sheet but trying to rebuild what they have. Alongside them, we wanted to identify the technology companies that are helping others to succeed by providing them with new software tools.

Despite trailing behind the US, Europe is home to some highly disruptive companies: Revolut and Raisin in financial services, as well as Booking.com and Amadeus in travel, for example. We also tried to find organisations applying new technologies to social problems, and individuals who have led digital change. Lastly, we included a category for digital training providers, given the reskilling need.

After a call-out for nominations last summer, we received a gratifying 4,000 entries. They were incredibly varied, from the tiniest to the largest company. Entries ranged from ThyssenKrupp’s elevator technology to small dental surgeries talking about setting up a Facebook page. More than a quarter of the submissions were from small companies.

Going online is no longer a radical step for most organisations, but it remains an experiment for some. Stilo e Stile is a pen shop in Rome that was saved from going out of business when the owner’s son set up an ecommerce presence for the first time. The shop started selling through platforms including Google, Amazon and eBay. Its owner, Mario Pagnozzi, wrote of the experience: “The transformation of a familiar business is not easy. Think about a 50-year-old. One day her shop changes and she begins to study web marketing, how to ship a pack, how to write content for an online website. The journey changes and you see with your eyes that’s the only way to save your business, so you start to study again like a child. Open mind is the only [thing that] can save you.”

We heard a similar story in many nominations. A son or a granddaughter had joined a family business and thrust it into the 21st century. One example was Asti Technologies in northern Spain — Verónica Pascual had turned her family engineering company into a pioneer of Industry 4.0.

It is impossible to compare these enterprises directly with Europe’s largest industrial companies, such as Airbus and Spanish bank BBVA, both of which deploy sophisticated technology in product design. The final list is best regarded not as recognition of one quality but as a snapshot of how Europe’s economy is evolving in various ways, aided by technology.

The costs of disruption — job losses and in some cases work casualisation — were a topic of keen debate when the judges gathered in Brussels. A prime example was Deliveroo, the UK delivery company valued at about $2bn. Although it was admired for its rapid growth, its treatment of drivers and riders as self-employed contractors for whom it takes limited responsibility was heavily criticised (Read about the judges’ dilemma here).

In terms of training, many nominated projects focused on women and girls or on training refugees and migrants. There was less evidence of training or reskilling of older workers whose skills have dated because of technology. The judges hope to see a deeper response to a huge challenge in the future.

Europe has a fair way to go to match the sense of opportunity and the availability of growth finance in the US. While Deliveroo and others, including Adyen, the Dutch payments company, have become European “unicorns” valued at more than $1bn, they are heavily outnumbered in Silicon Valley. European growth companies are still lured to the US to expand.

But the Road to Growth project uncovered a huge range and variety of activity from European companies and entrepreneurs. One of the key insights was how much is going on in industries that do not grab headlines as readily as consumer internet and social media groups. These ranged from health groups such as Cambridge Cancer Genomics in the UK to supply chain businesses such as Imperial Logistics in Germany.

There is plenty for Europe to be proud of, much of it involving cutting-edge technology applied in ways that are transforming industries. As well as accelerating its pace, the continent should shout a bit louder about what it is achieving. Those on the Road to Growth list are making themselves known.

Comments