Best of oasis: Louis Barthélemy’s Egyptian-inspired creations

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Last spring, the Paris- and Marrakech-based French designer and illustrator Louis Barthélemy found himself grounded in Egypt. Not that he was unhappy about it; several years earlier, after stints designing textiles for the likes of Gucci, Dior and Salvatore Ferragamo, he had followed a romantic interest to Cairo, and subsequently fallen hard for the city itself – its dusty bookstores, its faded art deco buildings, its secret gardens. And its talented artisans: wandering the Souk El-Khaymiya (“Street of Tentmakers”), he stumbled upon a tiny atelier specialising in the dying art of khayameya, a craft akin to quilting involving ornate appliqué patterns sewn onto plain cotton canvas, which is used to adorn the interiors of tents.

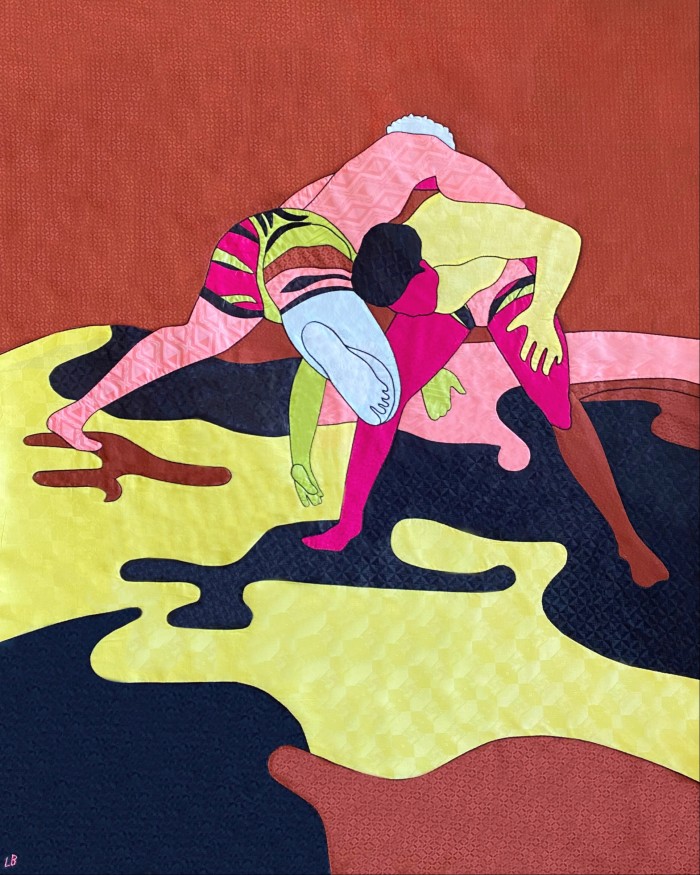

The relationship eventually ended, but Barthélemy’s love affair with Cairo and khayameya endures – the designer returns regularly for weeks at a time to work with artisan Tarek Abdelhay Hafez Abouelenin to create large-scale khayameya tapestries. Showcasing Barthélemy’s whimsical illustrations of native birds, trees and Ancient Egyptians capriciously transposed into contemporary settings – a gym, a Parisian cabaret – the pieces have been exhibited in Beirut and Cairo and feature in private collections from Paris to Marrakech to New York.

Barthélemy is one of several contemporary designers, such as Moroccan-based Laurence Leenaert of LRNCE and Noé Duchaufour-Lawrance in Portugal, who work rather like anthropologists – experimenting with, conserving and supporting specialised artisanal craft techniques. For some, Barthélemy included, the pandemic allowed for more time not just to follow through on deferred projects, but to engage in a bit of creative free association. In fact, while stranded in Egypt, Barthélemy managed to establish not one but two lifestyle brands. The first, called Udjat (a word that represents the protective eye of Horus), consists of hand-crafted objects, accessories and clothes inspired by Egyptian history and craft; already available (in a limited capacity) online, it’s scheduled to physically launch in the gift shop of Cairo’s newly renovated Egyptian Museum at the end of 2021. The second, an eponymous fashion-art-accessories line, will launch next month.

It’s not a stretch to say Udjat was inspired by an impromptu extended stay at the site of a legendary oracle in the Egyptian desert. In late March 2020, Barthélemy took the advice of Cairo-based entrepreneur and designer Laila Neamatalla and decamped to Siwa, an ancient oasis nine hours’ drive west of the capital, not far from the Libyan border. Thought to have been settled as far back as the 10th millennium BC, it is the home of the Temple of Amun, which honours the god who was consulted by Greek kings (Alexander the Great was said to have followed birds to the oracle).

In more recent times, Siwa – predominantly populated by Berbers – has become an insider travellers’ pilgrimage destination, thanks to Adrère Amellal, the resort built like an ancient village at the foot of a dramatic limestone hill among sand dunes and salt lakes. Owned by the respected environmentalist Mounir Neamatalla (who is Laila Neamatalla’s brother), the property eschews electric lights in favour of oil lamps and candlelight.

Neamatalla is also the founder of EQI, an agency that consults on sustainable projects in north Africa and the Middle East; he has spearheaded myriad other initiatives in Siwa’s environs, including a second eco-property, the Albabenshal Lodge; a women’s craft collective; and the restoration of several historic monuments, including the Shali Fortress.

Barthélemy spent the first weeks of his desert sojourn exploring Siwa and introducing himself to local craftspeople, with the help of a friend, Haneen Afr, who served as an ad-hoc translator and design assistant. “I thought I was going to spend just a few weeks there,” Barthélemy said with a smile, “but it ended up turning into five productive and inspiring months.”

Over those months, galvanised more by curiosity than commercial aspirations, Barthélemy and Afr had the opportunity to experiment with local materials and craft techniques, resulting in a prolific collection of prototype objects. They tracked down a local who made baskets from palm trees; Barthélemy collaborated with a limestone carver on a series of sculptures based on his own drawings of Egyptian deities. Barthélemy and Afr also dove into the craft of salt carving – very typical of Siwa, which is surrounded by salt quarries and lakes. “Every day I went to one of the salt lakes and scrubbed myself clean,” recalled Barthélemy. “It felt divine. Salt is such a beautiful material to work with because it’s so purifying and, more esoterically, it is thought to emit positive energy.”

With salt rocks extracted from the lakes, Barthélemy created a monumental table, as well as candle holders and a collection of beads and amulets. With several local female ceramicists from the EQI-supported craft collective, he developed a salt glaze and created an array of bright white vessels inspired by the shapes of ancient amphorae.

When a physical outlet for showcasing their creative endeavours presented itself at Cairo’s faded Egyptian Museum, Mounir Neamatalla proposed to Barthélemy that he help to create a brand – both inspired by and made in Egypt. Thus Udjat was born.

Barthélemy’s own eponymous brand was also hatched in the Egyptian desert, but it germinated during his past life as a textile designer in Paris. At one of the prestigious fashion brands Barthélemy worked for, a colleague had helped to develop a collection of exceptional cashmere fabric woven by artisans in Nepal. But when the time came to promote the pieces made with this material, the marketing team opted not to cite its Nepalese provenance.

“I did not relate to this decision at all,” said Barthélemy. “I felt that we should have celebrated not just this unique product, but where it came from. Luxury goods should not exclusively be associated with Italy and France. In the distant past, the Silk Road was where valued, luxurious objects from all over the world were traded. And that was the beginning of my realisation that I needed to define luxury in my own way.”

Many luxury fashion houses have since come round to his way of seeing things. Barthélemy is currently working on kaftans, swimwear, T-shirts and jackets with appliquéd khayameya work for Emporio Sirenuse, the Positano-based lifestyle brand designed by Carla Sersale and Viola Parrocchetti. Christian Louboutin – whose biological father is Egyptian – commissioned Barthélemy to create a ceiling for his flagship store in Paris elaborating one of the designer’s large-scale khayameya pieces. He’s also working on a line of bags, sneakers and high heels for Louboutin featuring prints inspired by the ceiling.

Barthélemy’s new brand may be eponymous, but he actively shares the credit – and profits – with the people with whom he works. “The finished works are really just objects of love,” said Barthélemy. “What really matters to me is the process and journey behind the making of it – my interactions and dialogues with the artisans. The moment an object is finished, I don’t feel the need to have it. It’s more important to me to live the story behind it.”

udjategypt.com. louisbarthélemy.com launches in mid-June

Comments