US bond sell-off stirs warnings over stock market strength

Simply sign up to the US inflation myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The drop in US government bond prices in the opening weeks of 2021 poses a threat to Wall Street’s record run, analysts and investors have said.

High prices and vanishingly slim yields on Treasuries have provided a key support for equities since the shock of the coronavirus outbreak last year. But, stung by expectations for rising inflation, yields have swept higher, with the 10-year benchmark yield briefly touching 1.3 per cent this week, from a little above 0.9 per cent at the start of the year. Already, February is shaping up to provide one of the biggest monthly increases in yields since 2018.

Investors are now scrambling to identify the potential tipping point for equities.

“If we see a gradual increase in yields over the course of this year and next year, that is something the equity market is happy to digest,” said Kiran Ganesh, a multi-asset strategist at UBS Global Wealth Management. “If things happen a bit more quickly . . . that could lead to more substantial problems.”

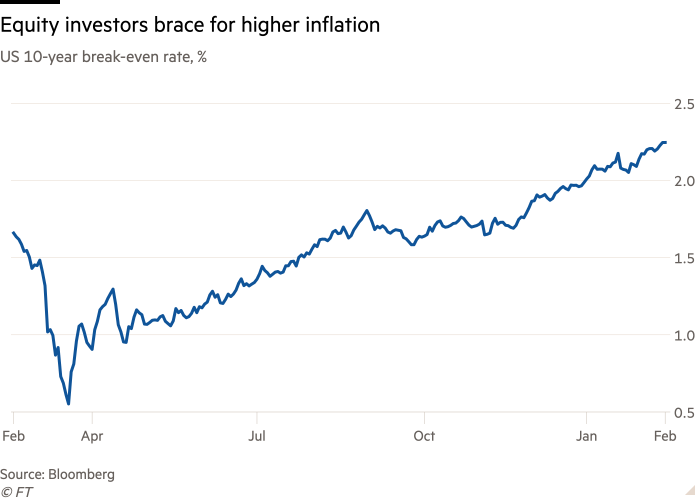

The prospect of a $1.9tn stimulus package coming out of Washington, pent-up demand from months of social curbs, and loose monetary policy from the Federal Reserve have pushed inflation expectations to their highest in years. One metric derived from US inflation-protected government securities — the 10-year break-even rate — recently rose to its highest point since 2014, at 2.2 per cent.

So far, however, the core personal consumption expenditures price index, the Fed’s favoured measure of inflation, stood at 1.5 per cent as of December, below the central bank’s long-term target. In January, the core consumer price index, another measure of inflation, was flat compared with the previous month.

Inflation is kryptonite to bonds, eating away at the value of their fixed payments to investors.

For stocks, moderate inflation is typically a good thing. Sean Markowicz, an investment strategist at Schroders, calculates that US equities tend to outperform 90 per cent of the time when inflation is low but rising. Any inflation stemming from a return to normal life would also be a welcome sign that the US economy is slowly dragging itself out of its pandemic-induced slump.

Stocks may also prove more robust than in previous inflationary episodes. Yields remain low by historical standards. Crucially, the Fed has also made it clear it is happy to allow inflation to simmer without raising interest rates. But investors warn too swift an increase in prices could still knock some froth off stocks that are hovering around record highs, particularly in the red-hot tech sector.

A sharp rise in inflationary pressures may offset any nominal revenue increases as companies’ input costs rise too, squeezing profits. A rise in rates could also reduce the present value of companies’ future cash flows, denting equity valuations.

“The market will often discount those future cash flows at a higher rate when inflation rises to compensate for the fact [that] they are worth less in today’s money,” Markowicz said.

The task now is to figure out when those dynamics may kick in, investors said.

“It’s a pretty difficult number to put your finger on,” said Jeffrey Palma, head of public investments in State Street Global Advisors’ global fiduciary solutions group. But, the break-even rate rising “substantially” above 3 per cent would “get to a point on the curve where equities become a little less settled”.

Goldman Sachs analysts recently calculated, based on historical data, that it would take a 0.36 percentage point increase in rates over a month for equities to wobble. Deepak Puri, chief investment officer for the Americas at Deutsche Bank Wealth Management, said he thinks the yield on the 10-year Treasury “needs to be in my mind at least above 1.75 per cent to start really making a dent in the equity market’s structural argument that it’s the best place to be”.

If inflation expectations remain upbeat, they could help to rebalance stock markets, sapping high-growth sectors like technology while boosting long unloved sectors such as financials and energy, which are typically more positively correlated with rising inflation.

“The broad theme is that you want companies that are most cyclically exposed,” said Jonathan Golub, chief US equity strategist for Credit Suisse. “An improving economy helps those companies that are perceived to be weaker.”

A reckoning could come as early as this summer, investors said. They forecast the economy to come roaring back by then, fuelled in large part by an additional injection of fiscal stimulus. Treasury secretary Janet Yellen recently reiterated the need to “go big” on fiscal support to shore up the US economy. And Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell has stressed his commitment to “patiently accommodative” monetary policy.

“There is going to be a moment in the summer where we have above target and rising inflation, a strong GDP print, interest rates close to zero and monetary policy being pumped in,” forecasts Ganesh. “The Fed is telling us it is going to be fine, and we think it is going to be fine . . . but that is likely to lead to nervousness.”

Golub said that nerves could give way to prolonged pain for equity investors, especially if the acceleration in consumer price increases becomes unruly.

“If [inflation] starts running away . . . the market would perceive it very very badly,” he said. “All of a sudden, the party is over.”

Comments