British architecture cannot afford to remain an old boys’ club

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Women like me were not supposed to be architects. It was the early 1970s in Brixton. I was 18 with a lovely new baby and A-levels on the horizon. Home was a room and kitchen, with my partner, in a condemned bedsit. The health visitor was kind as she delivered her verdict on my chances. “You won’t make an architect, dear,” she said. “It’s quite impossible. My son’s been trying for years. He hasn’t made it — and he’s white.”

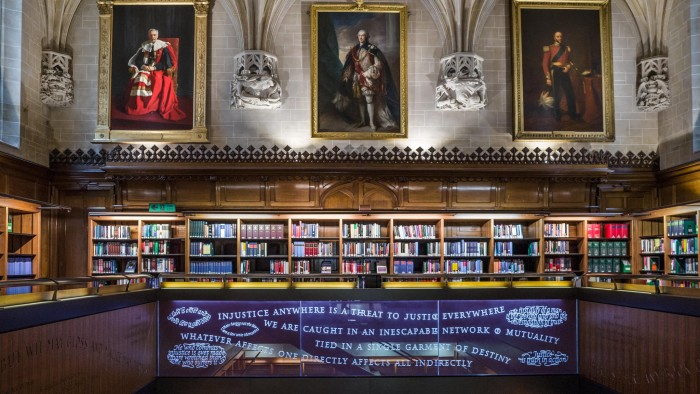

Forty-five years after that warning — the seven-year qualification complete, many enjoyable community housing projects built and, having co-designed the refurbishment of the UK Supreme Court and London’s Green Park tube station, I am happy to say that the profession is changing. But not fast enough.

Architecture has deep-rooted diversity problems. As the world changes around us, the profession that shapes our lives cannot afford to remain the same old boys’ club. To get to grips with 21st century problems, we need to modernise and throw open the doors to talented women and men from all backgrounds. Yet the risk-averse industry clings to customs harking back to the days when the Royal Institute of British Architects, the professional body, was established in the 1830s under the patronage of William IV.

Those of us who speak out face intimidation from the Riba establishment. Last month I was sent a “cease and desist” letter from Riba after I asked questions at a hustings for the forthcoming presidential elections, in which I am a candidate. I had questioned the chief executive’s salary, sky-high student fees and low average wages for post-qualification architects. The information I quoted had been publicly available for years on the Charities Commission website, as well as published in articles and discussed for months on social media. I had also made other allegations against Riba, which it said were unsubstantiated and damaging.

The case for reform is a powerful one. The sector has an estimated annual turnover of about £3bn in the UK. Spanning urban planning and infrastructure as well as design of homes and offices, it will only grow more important in the run-up to leaving the EU and beyond. It is also one of the UK’s leading cultural assets, exporting services worth about £474m in 2016. British architects are at the cutting edge of the global industry — from Lord Richard Rogers, whose 3 World Trade Center opened last month; to Sir David Adjaye’s Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture; and the late Dame Zaha Hadid’s Maxxi museum in Rome.

Moreover, architectural expertise can solve some of our country’s most intractable political problems, from how we balance the need for building efficient infrastructure with the rights of local residents — the crux of the two-decade debate over the third runway at Heathrow — to how we build the affordable and accessible homes needed to ease increasing levels of “housing stress”. And those homes need to be safe: the inquiry into last year’s tragic fire at Grenfell Tower demonstrates that cost-cutting at the expense of quality in design can prove fatal. Architects with a wide range of experiences and perspectives have a role to play here.

Design and construction techniques are on the cusp of digital transformation. Architects can lead that change. Drawing boards and blueprints have been replaced by computer-aided design (Cad) and the promise of artificial intelligence. Virtual studios and drone surveys will soon be reality. I already enjoy the ease of digital collaboration with colleagues overseas, especially in the many Commonwealth countries with design skills shortages.

Collaborative architecture needs the nimble minds and flexibility I see in many young graduates, who seem unhindered by cultural preconceptions. My British-Nigerian artist client Yinka Shonibare says: “I’m not disabled, I live in a disabling environment.” Inspired by that, the young people in my practice have created a barrier-free design in which the wheelchair ramp becomes an enabling, comfortable light-filled space.

However, much of the industry remains stuck in the 19th century. Today, a few large practices dominate, many of which are run by older, upper-middle-class men who favour employing ranks of so-called Cad-monkeys. These often unwelcoming studios are out of kilter with today’s design culture. Surveys by the Architects’ Journal and the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust this year show disappointment about “institutional discrimination” and bullying against under-represented groups: women, black and minority-ethnic, and LGBT people.

Nevertheless I am optimistic. Although change discomfits many in architecture’s establishment, the gilt-framed paintings of grey-whiskered eminences now languish in basement rooms of Riba’s headquarters. Riba’s schools programme is teaching budding architects and my own incubator programme, launching soon in Mr Adjaye’s wonderful building for the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust, will support young architects from diverse backgrounds as they start new practices.

I like to think a health visitor today, meeting an 18-year-old woman in a situation similar to mine, would say, not: “An architect? Impossible” but “An architect? Yes indeed!”

The writer is a candidate for the presidency of the Royal Institute of British Architects

Comments